By Kathryn Bold

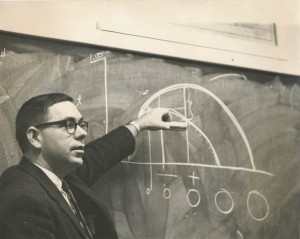

It was the winter of 1964, and James McGaugh already had what he considered a dream job. He’d earned a doctorate in psychology at UC Berkeley in 1959, taught for a few years at San Jose State College, done some postdoctoral work in Rome for a year, and then landed at the University of Oregon teaching and researching how the human brain works. “I was treated like a little prince up there,” McGaugh says. “They gave me everything I wanted. … I loved it there.”

Then the phone rang. McGaugh’s dissertation adviser from Berkeley was on the line, telling him about this new campus the University of California was creating on empty pastureland in a place called the Irvine Ranch. He suggested McGaugh put his name in to become the founding chair of an interdisciplinary department to study the brain and behavior.

It would be “the very first one in the world. And I was 32 years old,” says McGaugh, who followed the advice and was offered the position. “For a 32-year-old kid to get the opportunity to create a department of this kind – and to have full responsibility for that – I mean, that’s just mind-boggling. And I took it.”

He never left. As UCI nears its 50th birthday, McGaugh is one of only a few of those founding faculty and administrators who are still productive members of the campus community. His role has ranged from teaching to research to administration – he was executive vice chancellor for a while and is a co-founder of UCI’s Center for the Neurobiology of Learning & Memory (cnlm.uci.edu). But at heart, McGaugh has been a researcher, doing groundbreaking work on how the brain creates memories, which earned him election to the National Academy of Sciences.

It was work, he says, that he couldn’t have done anywhere else. Had he stayed in Oregon, McGaugh “probably would have been isolated and, over the long haul, … gravitated into teaching” and left research. “This was really, really good for me. Just amazing. Hell of a ride,” he says of his career at UCI. “I couldn’t have achieved, I don’t think, what I’ve achieved at any other place. I mean, it’s just incredible.”

At the age of 82, McGaugh remains active in his field, making regular trips to conferences and working within the CNLM. His continued involvement with UCI gives him a rare vantage point from which to view the university’s evolution from open ranchland to top education and research institution with more than 29,000 students, 1,100 faculty members and 9,700 staff members.

Rounding up the team

McGaugh arrived at UC Irvine in June 1964, about 14 months before the campus would open for its first students. His job was to recruit teachers and researchers for the new brain and behavior department (later called the Department of Neurobiology & Behavior), develop the curriculum and begin managing what would become one of the premier programs in the nation.

It was a position that held bright promise but also carried significant risk for a young research scientist – a risk McGaugh says he didn’t fully appreciate at the time.

It was a position that held bright promise but also carried significant risk for a young research scientist – a risk McGaugh says he didn’t fully appreciate at the time.

“I was not sophisticated enough to know that it could have been the end of my scientific career, because that’s a heavy administrative load,” he says, sitting in his sun-drenched corner office in the CNLM’s Qureshey Research Laboratory. “But it was not the end of my scientific career, so I had a good time afterward. Those were wonderful days – terrific days.”

McGaugh recalls a relatively small cadre of administrators and faculty working to launch the university for the 1965-66 academic year and to foster its growth in the ensuing years. UC regents intended UCI to reach parity with UCLA, UC Berkeley and the other existing campuses, so recruiters for the Irvine campus targeted top talent.

“All of the deans who were eligible for the National Academy of Sciences when this place was founded were elected to the National Academy of Sciences after they got here,” McGaugh says.

Three of the early wave of faculty – Leland H. Hartwell, Frederick Reines and F. Sherwood Rowland – went on to win Nobel Prizes, though Reines’ was for work on neutrinos that he did before arriving at UCI and Hartwell’s was for work on cell growth after he left. Rowland’s Nobel recognized his discovery – at UCI – that man-made chemicals were eroding the Earth’s atmospheric ozone layer.

Blazing the trail

“We were just loaded with outstanding leadership, very high-achieving people who had positive outlooks on what [UC Irvine] was going to be,” McGaugh says. “The optimism was just around. It was fun.”

He credits some of those visionaries with laying solid groundwork and making pivotal hiring decisions.

Founding biological sciences dean Edward Steinhaus, he says, was instrumental in developing the biological programs and changing how universities structure the study of sciences, opting for an interdisciplinary approach over the traditional and more isolated “silo” approach.

“He originated the organization of biological sciences as it is today, divided in terms of levels of analysis rather than the kind of animals or plants that people work on,” McGaugh says, adding that UCLA and UC Berkeley eventually adopted a similar model. “He was really an intellectual pioneer.”

Surprisingly, McGaugh says, he and the other administrators had little trouble attracting new hires to a campus that at the time barely existed. That newness, he believes, was part of UCI’s appeal.

“Nobody turned me down,” he says. “There was an infectious excitement about what we were doing here. It was almost like summer camp.”

Riding high

Tight friendships grew, a function of relative geographic remoteness and a shared sense of mission.

“We knew each other, and we felt we were building something,” McGaugh says. “And now it’s much more isolated than that. I don’t have a sense of building or the campus. I only have a sense of what my department is doing and what the center is doing.

“I don’t know what’s happening in sociology. I don’t know what’s happening in English or history or engineering. I used to know all of that, but I don’t anymore because the campus is too big. I mean, there’s nothing bad about that; it’s just a natural consequence.”

The modern UCI is mostly what the young McGaugh had hoped it would be – the differences due to the campus’s evolving mission, the decreases in state funding for higher education and radical changes in Orange County itself. UCI is ranked first among U.S. universities under 50 years old – and seventh worldwide – by the London-based Times Higher Education, and it often places 12th or above in national evaluations of public universities. Still, McGaugh sees room for improvement.

“If you look at where we’re ranked and what we’ve achieved across campus as a now well-established university, it’s damn good,” he says. “We have really built a great university. Is it as great as I would like it to be? The answer is no. And I think there’s no reason we couldn’t rank No. 2 or No. 3.”

Images provided by UCOP and UCI Communications.